In the race to solve the family health crisis, B.C. is absolutely crushing Ontario. Here's the data.

The sight of hundreds of people in Walkerton, Ontario, waiting hours in the cold to sign up with a new family doctor shows just how dire the family health crisis is right now. The pandemic rapidly accelerated the family doctor shortage in all provinces, but the responses to this shortage have been very different. Ontario, for example, has at times denied that the physician shortage even exists. By contrast, the B.C. government introduced the longitudinal family physician (LFP) payment model in February 2023, which incentivizes physicians trained in family medicine to practice as LFPs.* Within a year, over 700 doctors newly took on LFP roles to address the growing issue of residents without a family doctor.

*Explainer: A longitudinal family physician (LFP) is what’s colloquially referred to as "my family doctor." Aside from being a LFP, a doctor trained in family medicine can also work as a hospitalist, in a walk-in, etc. A significant part of the family health crisis is not that there aren’t enough family doctors, but that these doctors are increasingly choosing to work in roles that don’t involve comprehensive long-term care of patients as their family doctor. Getting doctors to work as LFPs isn’t simply a shifting of resources; LFPs reduce the burden on the entire healthcare system by preventing the emergence and exacerbation of disease. Put simply, increasing the number of LFPs causes the system to become more efficient.

Anecdotally speaking, population growth is frequently blamed for the recent crisis in healthcare, but a comparison of Ontario to BC shows that this is a poor deflection. The growing family medicine crisis in Ontario, and the need for hundreds to wait in the cold while trying to hit the family doctor jackpot, is the result of poor decisions made by Ontario's policy makers. Here’s the data which backs this up.

Disclaimer: the data presented below uses CIHI's Scott's Medical Database (SMDB). However, the Ontario government relies on the Ontario Physician Reporting Centre (OPRC). Because each database uses different methodology to count the number of physicians, the Ontario government's communications will give numbers that are different than what's presented here. Regardless, SMDB is reliable for comparing the relative performance of one province to another, because the same methods are used in each province.

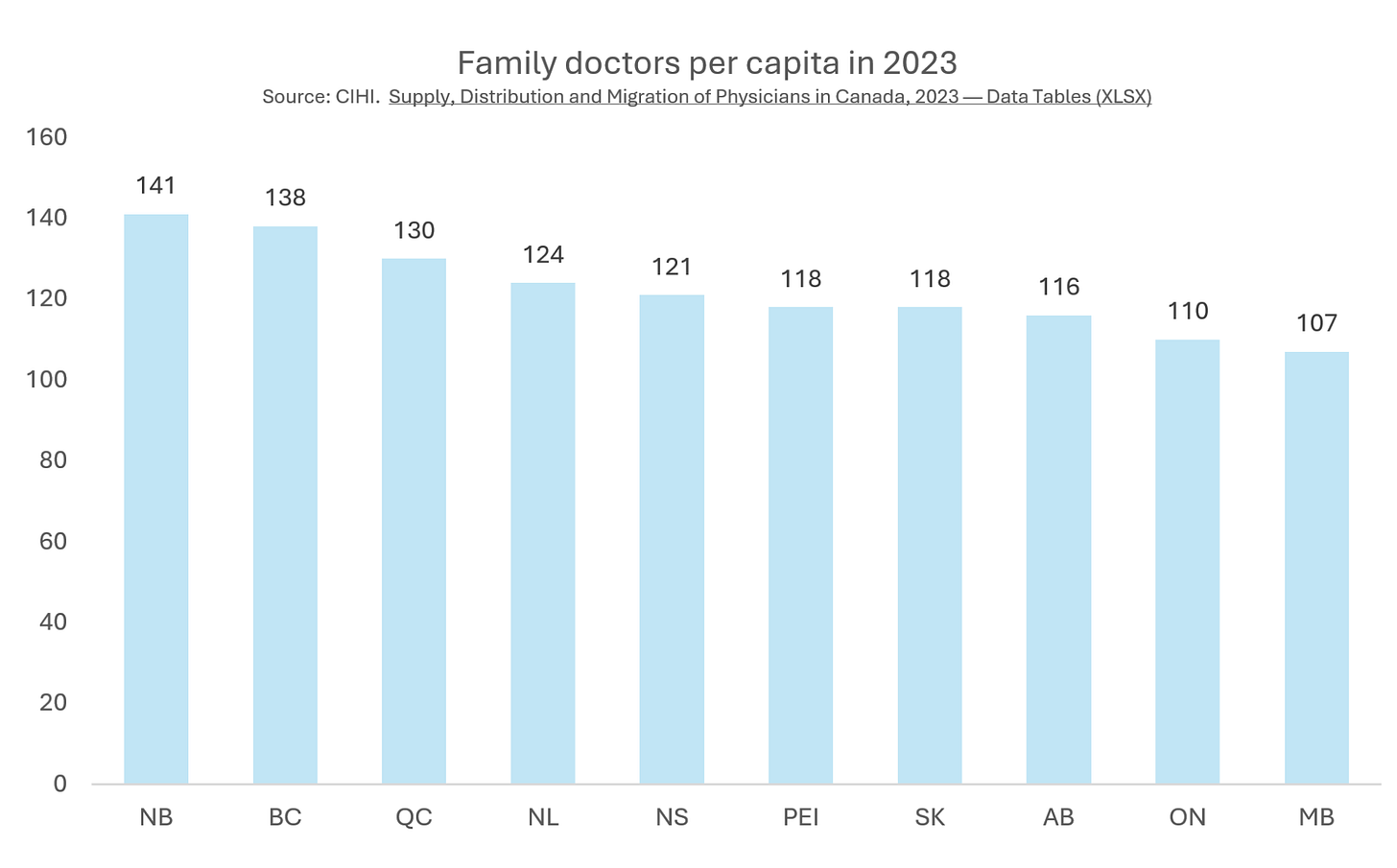

This is a very straightforward graph: NB and BC have the most family physicians per capita, while ON and MB have the least. However, a measure that uses the total supply of family physicians will depend on what happened in the pre-pandemic years, so it doesn't entirely capture post-pandemic responses.

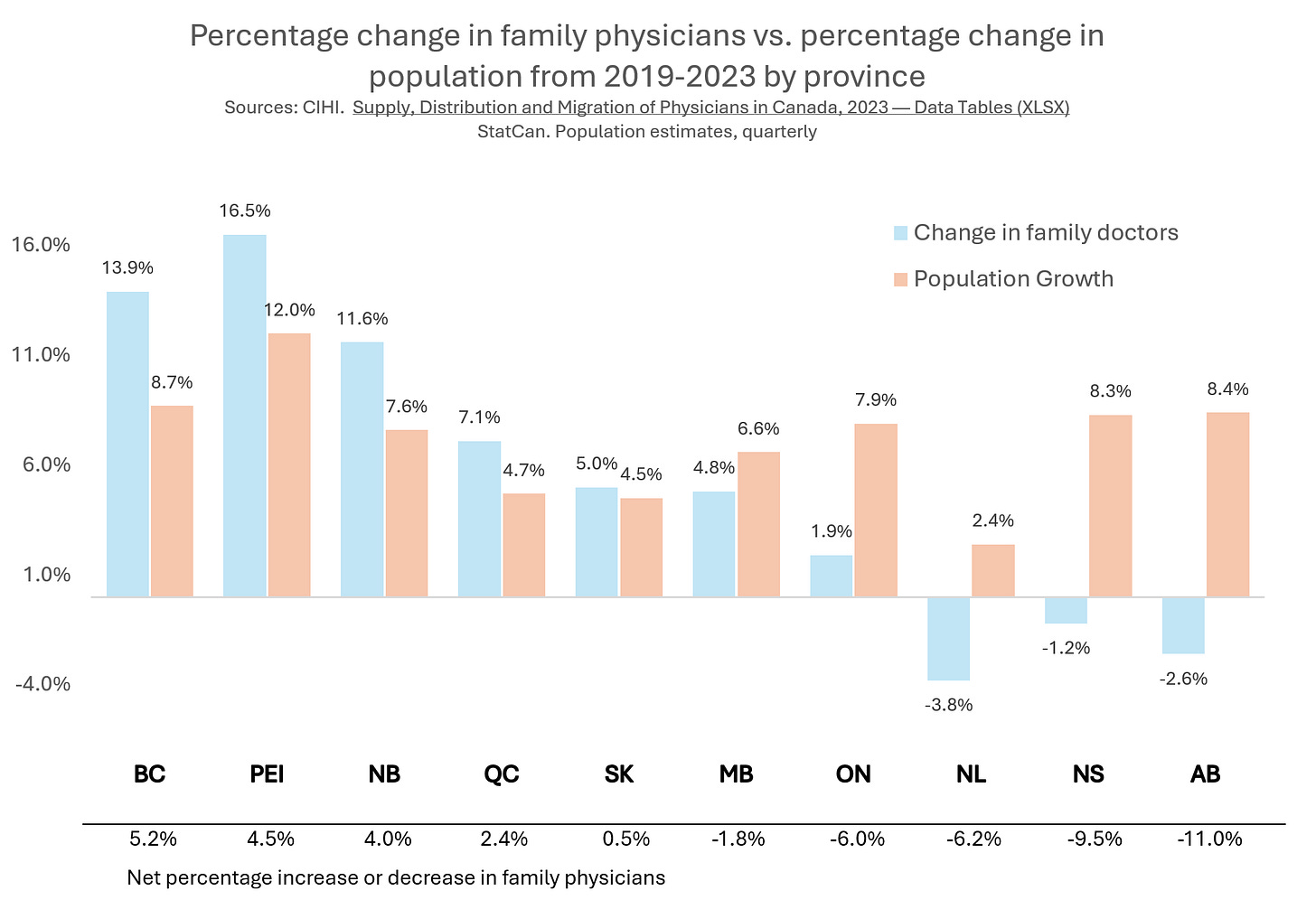

This graph more adequately captures the effect of the pandemic on family physician supply and subsequent efforts to respond to that. BC comes out ahead on this measure, though PEI and NB perform admirably as well. Half of the provinces, including Ontario, failed to grow their supply at the pace of population growth.

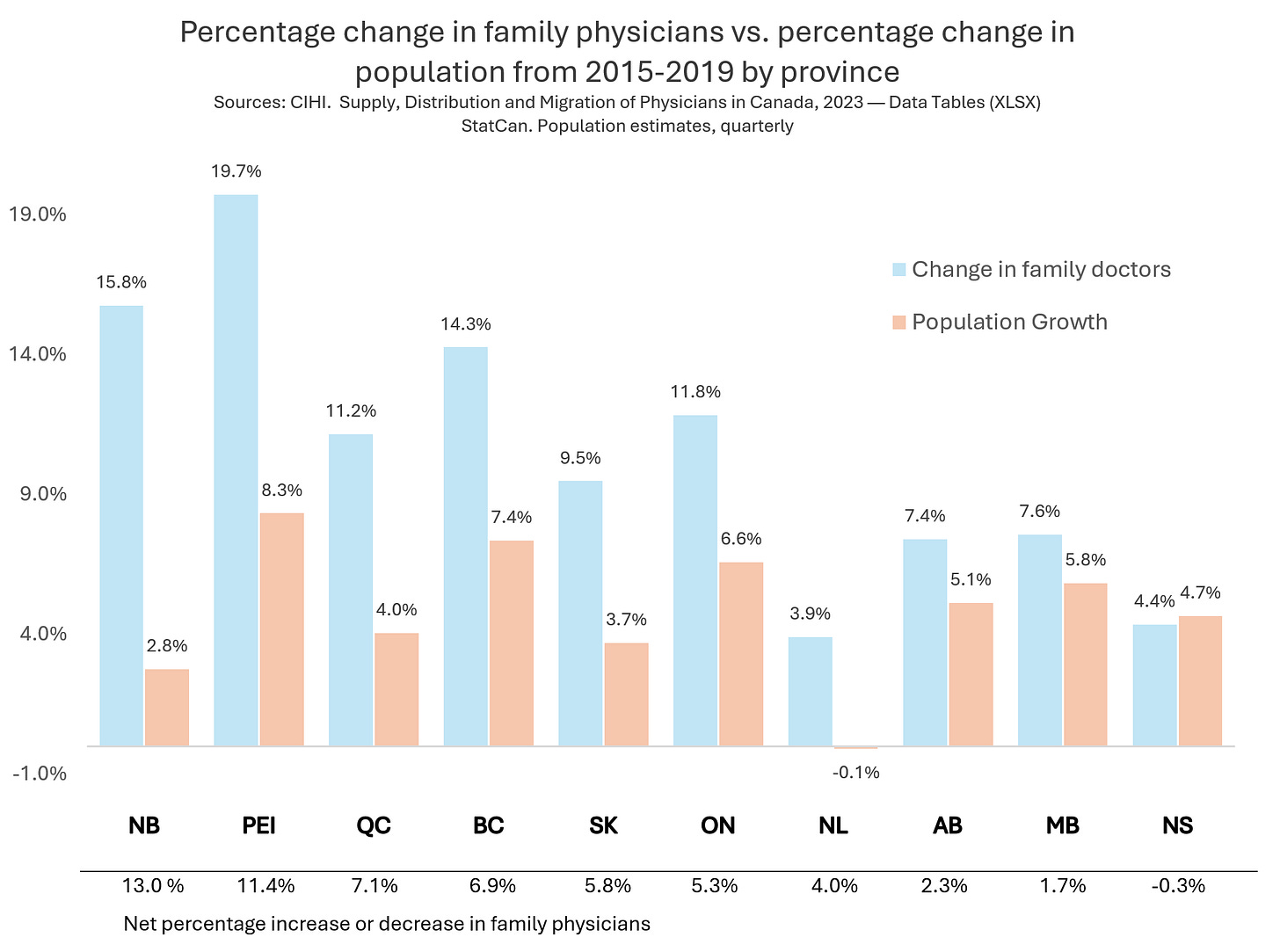

Looking at the pre-pandemic years shows that Ontario used to be more competitive with other provinces at recruiting and producing family doctors, and this is especially obvious when compared to the other large provinces of Quebec and BC. It is also apparent that BC has always been good at shoring up its supply of family doctors, but as noted above, this doesn't directly translate to the number of LFPs. Data on the number of family doctors practicing as LFPs is hard to come by, but data on how many residents don't have a family doctor is slightly more available, and much more relevant.

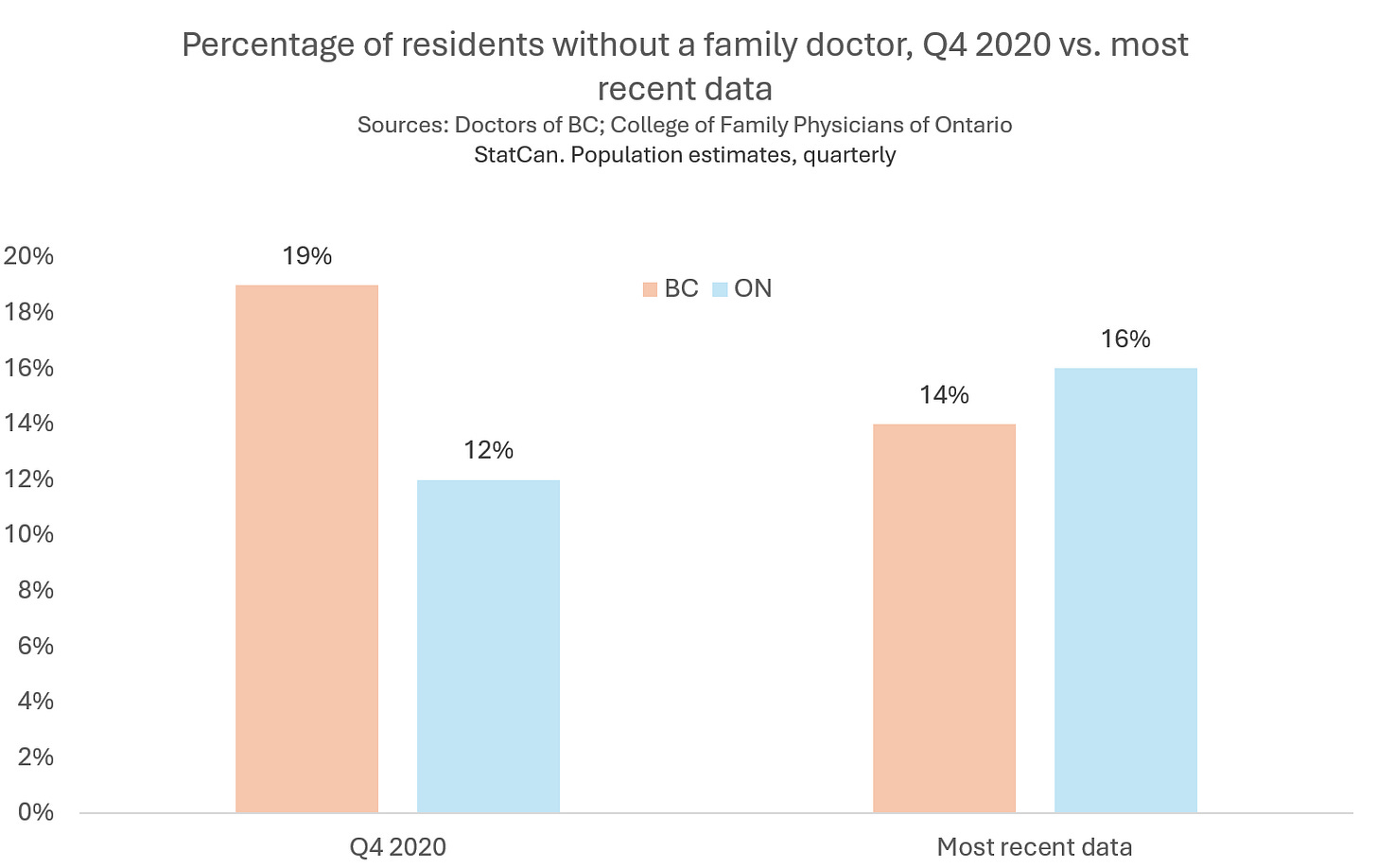

While BC started the pandemic with around 1 million residents not having a family doctor, Dr. Ahmer Karimuddin, president of Doctors of BC, believes that this was "now in the mid to high 700,000 number," in early 2024. On the other hand, Ontario started the pandemic with approximately 1.8 million residents not having a family doctor, but this had increased to 2.5 million in late 2023, according to data from the Ontario College of Family Physicians. This is all with the backdrop of higher population growth in BC, as shown in chart 2.

At this point, BC and Ontario have completely swapped places, and the rift is expected to widen. The LFP payment model and the pace of family doctor recruitment would mean that BC should continue to see the number of residents without a family doctor decline. Ontario is expected to go in the complete opposite direction, at over 4 million residents without a family doctor by 2026. This would be more than 25% of Ontarians without a family doctor.

Aside from enacting a LFP payment model, the Ford government could have pursued digital infrastructure innovations to reduce administrative burden (and would have saved the province on healthcare expenditures), expanded the use of team-based family health models, or brought forth a litany of other measures that his opponents are now proposing, but no such measures have been taken. Needless to say, the Ford government's policy response (or lack thereof) is the biggest problem for family medicine in Ontario.

Ontario has bad stats..however the fact that BC has the “,0,prestige” of over 200 mutilated young people in the guise of gender health …they don't win any points